Having a Puppy is Excruciating

Alexander and I got a puppy in February this year. We took her home on Valentine’s Day, which is fitting because I am stupidly (or should I say, cupidly) in love with her.

Her name is Egg and she is a very good Egg. In fact, she is a precious golden Egg. The best Egg in the world. I want her to have a very good and happy life. I want her to play with other dogs and go for walks and smell interesting things. I want her to run and rump and wrestle with her best friend, Max.

Up until recently that was her life; full of frolicking and cheeky puppy antics. But about two months ago, we noticed Egg limping around trying not to use her back right leg. Her limp didn’t get better after weeks of rest, pain relief and anti-inflammatory medication. We had some x-rays done and found out that Eggy had femoral head necrosis. There was no clear cause for the necrosis and the vet said she couldn’t do anything to stop the femoral head from dying. The only way forward was for Egg to have a surgery to get it removed. The vet explained that small dogs can function without the femoral head as muscle and scar tissue can form around the joint to stabilise it.

I was devastated to hear that Egg had an incurable condition and needed a surgery. I cried the whole way home. Like most mammals, I don’t like seeing others in pain. But seeing Egg in pain and knowing there would be more pain for her on the horizon was excruciating.

It hit me hard because I am responsible for Egg’s health and happiness, and instead of being happy, she was suffering. I wanted to magic her pain away. In fact, my strong preference is to protect Egg from any and all forms of discomfort.

But life is fucked like that. Being alive is riddled with discomfort and pain. Unfortunately, I can’t protect Egg from the experience of being alive because that would mean she would not, in fact, be alive.

Egg has had the surgery now and is sleeping lots and recovering slowly. Hopefully, in a couple of months, she will be able to run and rump and wrestle with Max again.

How do People Survive the Heartbreak of Having Children?

This whole experience with Egg has made me reflect on how excruciating it must be to be the parent of a human child. You could be the most attuned and supportive parent and your child will still experience physical and emotional pain. They will get hurt. There’s just no way of getting around it.

But man, I can imagine myself trying so hard to get around it. I would be at high risk of becoming a helicopter mum. I would need to constantly grapple with my urge to wrap my small human in cotton wool. My native impulse would be to shelter them from the inherent risk of being alive.

It would be a challenge to provide the right balance of developmentally appropriate protection/boundaries and developmentally appropriate autonomy/freedom. That balance would always be changing because children need both the containment of boundaries and the expansion of exploration – and they need different amounts of each in different ages and stages.

Infants, for example, are vulnerable and helpless. They cannot survive without the care and protection of their attachment figures. In this stage of development, caregivers are highly responsible for the wellbeing of their offspring. They cannot be 100% responsible as there are things outside of their control such as illness and accidents. However, they are definitely they major shareholders of responsibility in the life of their child.

Ideally this percentage gradually decreases as the child approaches developmental maturation or young adulthood. As children develop, they claim more freedom, agency and autonomy. They become more responsible for themselves and their choices. Over time, they buy out most of their parents shares of responsibility.

I remember [my daughter] asking me, when she was thirteen or so, what I believed the limits of my obligations to her were.

‘I believe I’m obliged to let you go,’ I said, once I thought about it, ‘but if that doesn’t work out, I believe I am obliged to remain responsible for you forever.’

- Rachel Cusk, Second Place (2021)

Until then, parents are tasked with the difficulty of providing the conditions of both safety and growth. Children should be protected such that they don’t fall too far or too hard too early (i.e. they shouldn’t be put in unnecessarily dangerous situations or left alone with overwhelming feelings) but at the same time they need space to make choices and attempt developmentally appropriate tasks. They need to try things and then fail and try again (i.e. the parenting motto “don’t steal their struggle”).

If I had a child, I would struggle with finding the right size for my sense of responsibility. I would feel guilt and anguish anytime my child got sick, scraped their knee or felt left out. And God help me if my imaginary child ever got their heart broken. I want to protect them from pain. I want to absorb their pain. I am a crazy person. Or as Byron Katie says, you can fight against reality but you will lose every time.

I know that if I had a child I would regularly get my heart broken, because I have the same hyperactive empathy/saviour complex in my other relationships. I have the tendency to take too much responsibility for other people’s emotions and to believe it is my responsibility to protect them from hard feelings. Sometimes I do this by downplaying or denying my own feelings, needs and desires. For a long time my growing edge has been feeling less responsible for others by trusting them to both tolerate and take responsibility for their feelings, needs, and choices. I felt some resistance to writing that because I want to distance myself from the neoliberal/new age doctrine of self-responsibility.

The neoliberal/new age doctrine claims that everyone is 100% responsible for their feelings, finances, health and for their ‘reality’. I think this is an extremely strange assertion given that we are a relational species living within interdependent social systems and ecosystems.

We cannot escape the truth that we are impacted by the systems we are born into and we have an impact on those systems. As embodied rather than ephemeral beings, it is impossible to live without a trace. We will consume and contribute and in all manner of ways alter the terrain in which we inhabit.

We Will Impact Others and Other Inescapable Truths

Of course I’ll hurt you. Of course you’ll hurt me. Of course we will hurt each other. But this is the very condition of existence. To become spring, means accepting the risk of winter. To become presence, means accepting the risk of absence.

- Excerpt from a love letter written by Antoine de Saint-Exupéry to Natalie Paley (1942)

So far in this article I have gestured towards a few inescapable truths. Here they are in raw form:

- Everyone alive is subject to physical and emotional pain (à la the first noble truth of Buddhism). This is the price of admission to our existence.

- Our existence will impact other beings and our environment. Just as we will impact others in beautiful ways, inevitably, there will be times when we invoke pain in other beings. Sometimes our impact will invoke beauty and pain at the same time.

- Knowing that all beings experience pain, and that we have an impact on our social systems and ecosystems, we have a responsibility to be compassionate and therefore mindful of our impact. Responsibility is the price of admission to relationality.

Attempts to Escape the Inescapable (and their consequences)

Look, I’m not a big fan of these truths. I find them unbearable at times and I regularly attempt to find loopholes. I try to protect myself and others from the inevitable experience of pain. I desperately try to avoid hurting others and I have an inflated sense of my own responsibility. In fact, my attempts to avoid the unavoidable generate some of the primary shaping forces of my identity:

Personality-wise: I’m a two in the Enneagram system – the helper/rescuer/people-pleaser type.

Politically: I’m a leftist, concerned about the harms of capitalism.

Vocationally: I’m a psychotherapist and facilitator.

Dietarily: I’m vegan.

Whilst I don’t want to reject any of these aspects of my identity, at some point I need to acknowledge what they are driven by. They are driven by my crippling fear of causing harm, my compulsive desire to be good and my hyperactive sense of responsibility.

There is a sweetness in these drives. How beautiful and wholesome that I don’t want to hurt anyone and that I want to be good and moral. Nonetheless, trying to escape inescapable truths is unsustainable. Further, my attempts to escape generate their own consequences.

Although it is honourable to minimise the harm I cause to others, it’s impossible to avoid it. There are consequences to trying to avoid harming others. For instance, in trying to avoid hurting others, do I render myself inert and impotent? Then, does my inaction end up causing more harm? This idea is fleshed out well through Chidi’s character in the Netflix series, The Good Place. Chidi is a philosophy professor who engages in moral calculus at every fork in the road and ends up crippled with indecision. Chidi’s indecision and inaction causes his loved ones a lot of frustration and pain.

Meanwhile, the goal of perpetually striving to be good contains its own violence; the violence of denying my shadow, my untempered desires and my own will to power. More often than not, beneath the compulsion to be good is the yearning to be loved and to belong. Yet the truth is, I don’t want to be loved for being good. I want to be loved in a way that transcends my goodness and badness, and encompasses all of me.

What then, are the consequences of my hyperactive sense of responsibility? Even though this one is simple, it’s taken me a long while to get it. Assuming too much responsibility for other adult humans is condescending as shit.

For example, within a polyamorous context I might refrain from sharing about a new relationship interest from a partner with the goal of protecting them from feeling hard feelings. In doing this, I have essentially decided that they can’t tolerate this news. This is the adult relationship equivalent of ‘stealing their struggle’.

If I’m really honest, I don’t withhold information to protect my partners from pain. I withhold information because it’s hard for me to tolerate other people’s pain and discomfort, particularly when I believe I am responsible for it.

My fear of causing harm, compulsion to be good and inflated sense of responsibility invoke caution, reticence and hypervigilance within me. Inadvertently, I deprioritise my desires, dull my expression and dampen my impact on the world.

Although my fear of hurting others looms large, it has not subsumed my desire to impact the world and to be impacted.

Leaving a Mark

I remember the first time a boy asked if he could give me a hickey. I thought it was hot that he wanted to leave a mark on me. It was so intentional.

In a way it has the same energy as carving your name into a school desk or wet concrete:

“Ari was here.”

Leaving a mark on the world is one of our most primal desires; from cave paintings, to graffiti, to the more abstracted footprint of a curated social media profile. From creating children, to companies, to political change: most of us are compelled to leave some kind of legacy.

We want to leave a little trail of breadcrumbs that serves as proof of our existence. When we look back at our breadcrumbs, we feel a little thrill of power and agency. Maybe that’s what Isaac felt when he looked at the hickey he made on my neck:

“I was here.”

Our impact on others is incredibly visceral in our sexual relationships. We can induce intense sensations, immense pleasure and even altered states in others through our bodies, our presence and our touch.

If everyone involved is into it, we can even leave a physical mark – a hickey, a handprint, a welt, a bruise. Consensual impact play has the potential to be a beautiful expression of agency, trust, power and responsibility. The blurred line of pleasure and pain within impact play illustrates the fact that our impact on others isn’t always black and white.

Impact play is not something I have explored in its more extreme forms. However, if I was to explore it, I can imagine I’d be more comfortable being impacted rather than holding the responsibility of being the impacter.

But the truth is, I want to impact other people and the world in ways that invoke pleasure, joy, freedom and deep connection. The power of being able to impact others comes with the risk of impacting them in ways that do not delight them. This is why I need to learn to tolerate the responsibility of being a human being who has an impact.

Turning towards and Tolerating Inescapable Truths

Until we know that we can bear the unbearable, we're always running scared.

- Ram Dass, One-Liners (2002)

If anyone needs tools to turn towards the inescapable truths of pain, impact, and responsibility, it’s me. Suffice to say, I’ve thought about this a lot. Following are three concepts and skills that can support us to tolerate the conditions of our interdependent existence:

- Enhancing the Window of Tolerance (Emotional regulation)

- Differentiation (Balancing relatedness and self-definition)

- The Dial of Responsibility – (Contextual flexibility)

1. Enhancing the Window of Tolerance

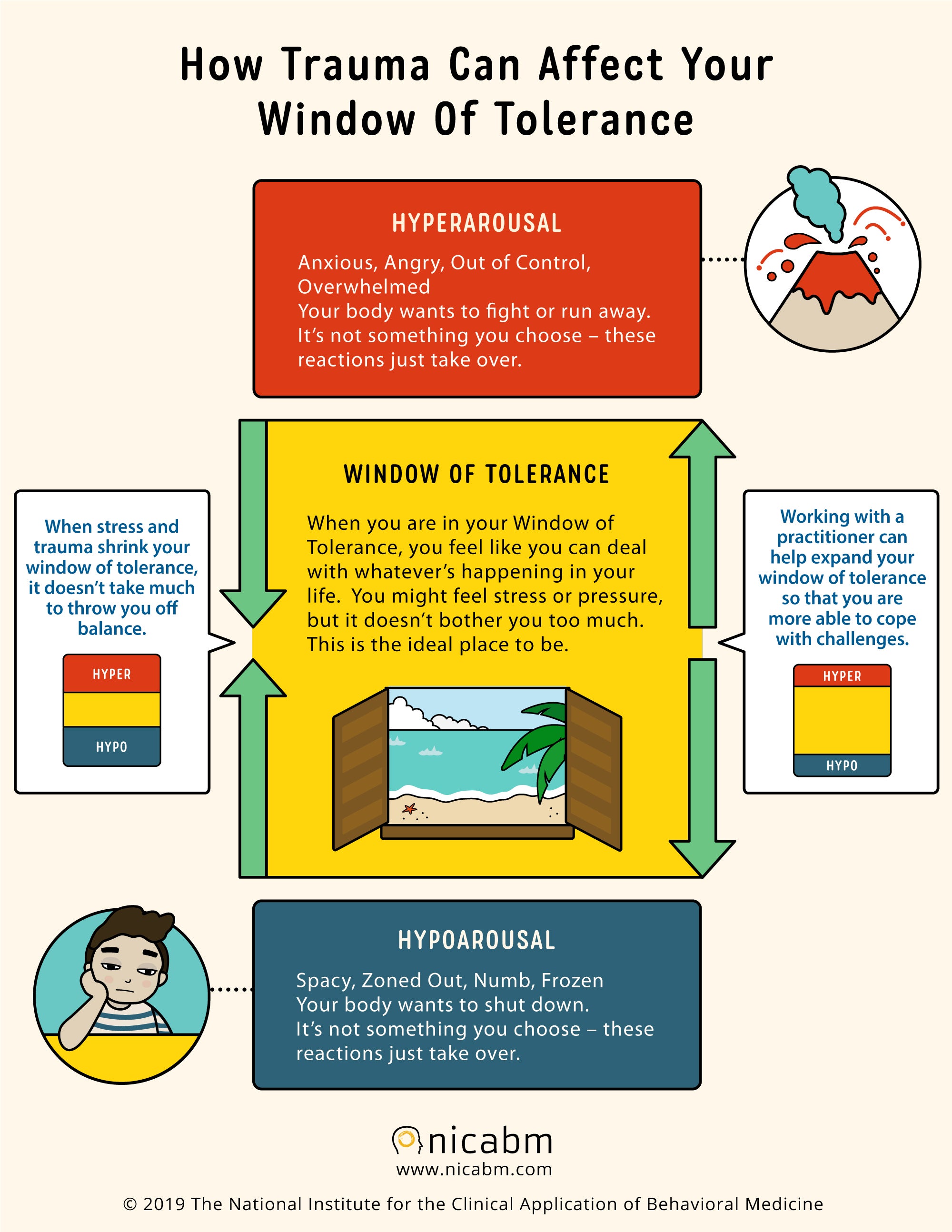

The term Window of Tolerance was coined by Dan Siegel in 1999. It refers to the range of affective arousal that a person can tolerate without flipping into hyperarousal (fight/flight) or dipping into hypoarousal (collapse/dissociation).

Image from https://www.nicabm.com/

When we are outside our window of tolerance our nervous system is overwhelmed or dysregulated. In these moments, we are unable to tolerate what we are experiencing and therefore we are unable to be present.

In contrast, when we are within our window of tolerance, our nervous system is in a state of regulation or equilibrium. This allows us to remain present, embodied and in connection even in the midst of intense feelings.

The size of our window of tolerance changes from person to person and from state to state. It is influenced from a multitude of factors such as temperament, neurotype, hormones, lifestyle, work and relationships. Experiences of trauma have a particularly significant impact on a person’s window of tolerance. This is especially the case if trauma occurs within the context of an early attachment relationships. Neglect and/or abuse from a caregiver disrupts the development of an infants’ regulatory capacity.

We learn to both tolerate different emotions and to self-regulate through co-regulation within our early attachment relationships.

For this reason, the treatment of trauma always involves the goal of expanding the client’s window of tolerance. There is a misconception that the treatment of trauma will make people feel less anxious, afraid, lonely or ashamed. However, once a secure foundation is established, the goal of trauma treatment is to support a client to gradually feel more whilst maintaining a sense of embodied and relational safety.

The goal of therapy is not to eliminate intense feelings, but to learn to tolerate them.

Expanding the window of tolerance is such a central component within psychotherapy because it seeks to enhance our capacity to feel a wider and deeper range of emotions. If we have a small window of tolerance, our natural impulse is to avoid the places, activities and relationships that overwhelm us. As such, our capacity to tolerate emotions directly impacts our willingness to engage with the world.

So, how do we expand our window of tolerance? I am undeniably biased, but I genuinely believe therapy is an incredible playground in which to expand one’s window of tolerance. However, this can and does happen in other relationships which have a foundation of safety and trust. In these safe relational containers, we expand our window of tolerance by spending time occupying the edges of our window.

How present can we be with our anger or anxiety before it becomes overwhelming?

How present can we be with our sadness or even shame before we collapse?

How present can we be with our joy and pleasure?

The role of the other person in this dynamic is to provide safety and co-regulation through their attunement, empathy and presence. The messages through this presence are: It’s safe to feel. It’s safe to be you. I’m not going to abandon you when you are feeling intense emotions. I’m with you. You are not alone in this.

A loved one’s presence and understanding in the midst of distress enhances our capacity to tolerate difficult emotions. Over time, this helps us to trust our capacity to tolerate distress even when we are alone. Co-regulation is the foundation of self-regulation. If we didn’t receive co-regulation as infants or children, we can experience the healing of co-regulation as adults.

I

Image from https://empoweredtoconnect.org/self-regulation/

Along with co-regulation, there are other strategies that can help us maintain presence and regulation when we are nearing the edge of dysregulation: engaging our senses – particularly in relation to nature, grounding self-touch, extending the exhalation, humming, sighing, postural shifts, movement and exercise.

Gradually, as we spend time in the edges of our window of tolerance without become dysregulated, our window expands - and our capacity to tolerate life expands expands with it. We become people who are able to bear that which was previously unbearable. We enhance our capacity to feel the intensity of life without dissociation, denial or drugs.

We can raw dog life.

2. Differentiation

As young infants, we have no separate sense of self. We are undifferentiated from our mothers. There is no such thing as my distress or mum’s distress, there is just distress.

Eventually, babies go through the phase of development where they like to use their arms to push away from their mother’s in order to look at them. They are beginning to realise they are other than their mother; a separate self. This is an early iteration of the lifelong process of differentiation.

The therapeutic concept of differentiation was refined by Murray Bowen in the 70s and formalised within Bowen Family Systems Theory. There are two main aspects of differentiation – intrapsychic and interpersonal. Intrapsychic differentiation refers to the capacity to differentiate between rational and emotional processes, such that one is not at the mercy of emotional reactivity. Interpersonal differentiation refers to the capacity to maintain one’s own boundaries, desires, and sense of self whilst in proximity with a loved one.

The opposite of differentiation is fusion. On an intrapsychic level, fusion occurs when we are outside our window or tolerance. In states of dysregulation, there is no capacity to reflect on our thoughts, feelings and nervous system responses because we are in them.

Interpersonally, fusion is the inability to maintain individuality and autonomy within a close relationship. The “I” becomes subsumed within the “we” or within the family system. These relationships suffer from emotional contagion – where the emotions of one person spread to other people in the relational system.

Bowen noted that there are two different ways of responding to interpersonal fusion. Some people with low levels of differentiation form co-dependent and enmeshed relationships. It is common in these relationships to try to control the other person in an attempt to manage one’s own anxiety. Other people respond to the anxiety of interpersonal fusion by cutting off from the relationship completely. This is evident in some adult children who move overseas to escape their overbearing parents. While cutting off from a relationship may help people to reconnect to their autonomy and separate sense of self, it does not increase their levels of differentiation. This is because they are not learning to maintain their sense of self whilst also being in connection.

People who have a differentiated sense of self are able to tolerate the dialectical needs of self-definition and relatedness (Blatt & Blass, 1992). In this way, differentiation is really just another way of describing secure attachment. Some people are able to hold the pole of self-definition, while others favour relatedness. If there is no balance, these preferences mirror the insecure attachment styles of avoidant/dismissive and anxious/preoccupied, respectively. Those who favour self-definition may inadvertently devalue relationality and herald a form of pseudo-independence. Meanwhile, those who favour relatedness may devalue autonomy and foster co-dependence in their relationships. Differentiation invites us to embrace the radical reality of interdependence.

As aforementioned, attachment relationships provide the foundation for our capacity for emotional regulation. Just as our capacity to regulate and trust others emerges within relationships, we cannot increase our differentiation on our own. We need to practice differentiation within the arena of relationships.

It can feel easy to own our desires and feel solid in our sense of self when we are alone. The challenge is, can we maintain our sense of self and communicate our desires to the person or people who matter the most to us?

Can we communicate our boundaries and desires whilst also making space for our loved one’s desires?

Can we tolerate the differences between self and other?

Can we stay in the vulnerability of connection, rather than squashing our truth or cutting off from the relationship to protect ourselves?

The message of the differentiated self is:

My boundaries, needs and desires matter, and so do yours.

I matter, and you matter.

Differentiation allows us to experience both self-definition and connectedness within our close relationships.

3. The Dial of Responsibility (Contextual flexibility)

Increasing our window of tolerance and levels of differentiation are both ways to tolerate the responsibility of our interdependence. Something else that has been supportive for me in this domain is learning to navigate the changing bounds of my responsibility from situation to situation. While our responsibility to others cannot be escaped, it can be refined and fine-tuned.

To this end, an analogy that I find helpful is imagining my sense of responsibility like a dial that I can turn up or down according to the relational context I find myself in. For example, in my relationship with Egg my sense of responsibility is dialled up pretty high. I am responsible for her.

"People have forgotten this truth," the fox said. "But you mustn’t forget it. You become responsible forever for what you’ve tamed."

- Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, The Little Prince (1943)

Whilst Egg is recovering from surgery, my responsibility dial is even higher than usual. I need to enforce boundaries and limit her movement so she doesn’t exacerbate the surgery site and injure herself.

However, there are other relationships where I could learn to dial down my sense of responsibility. I am speaking specifically about my relationships with other human adults. In these relationships, it’s okay for me to express my thoughts, feelings, needs and desires – even if doing so brings up difficult emotions for the other person.

However, this doesn’t mean mitigating my responsibility completely. Again, I’m seeking the differentiated stance that honours both self-definition and relatedness. This would mean being able to express what is true for me and listen with compassion about how that has impacted the person I’m relating to.

It sounds so simple but balancing these dialectic needs is not easy. It’s a dance in which the steps change from relationship to relationship and even moment to moment. The key is not letting our responsibility dial get too stuck on a single setting. We need our responsibility dial to be lubed up so we can turn it with ease whenever necessary.

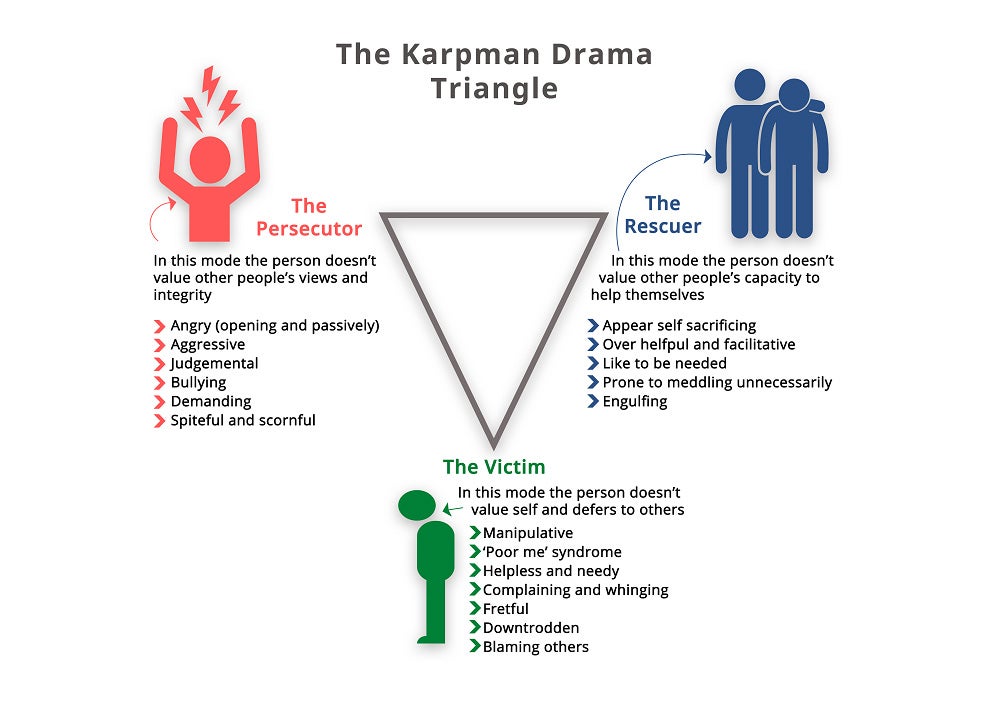

The Karpman Drama Triangle offers another useful framework when considering which direction to turn our responsibility dial.

Image from https://www.listeningpartnership.com/insight/about-the-drama-triangle-and-how-to-escape-it/

Different people may tend towards different points on the drama triangle. I’m a chronic rescuer which is why my direction of growth is dialling down my sense of responsibility for others and trusting other people’s capacity to tolerate the pain, discomfort and beauty of being alive.

People who have fallen in with new age/neoliberal doctrine of hyper-individuality sometimes land in the role of the perpetrator. This is a natural result of the adamant belief that people create their own reality and therefore deserve whatever happens to them. This group could learn to dial up their sense of responsibility, care and compassion for others.

People in the victim role lack a sense of agency, power and self-responsibility. This isn’t an active choice. Rather, it is a consequence of not having the emotional and relational resources that allow for the development of an empowered, competent and autonomous sense of self.

All three points on the triangle could benefit from increasing their window of tolerance, regulatory capacity and level of differentiation. This would support them to engage in the messiness of human emotions and relationships without resorting to unwarranted caretaking (rescuer), blaming and punishing (persecutor) or collapsing (victim).

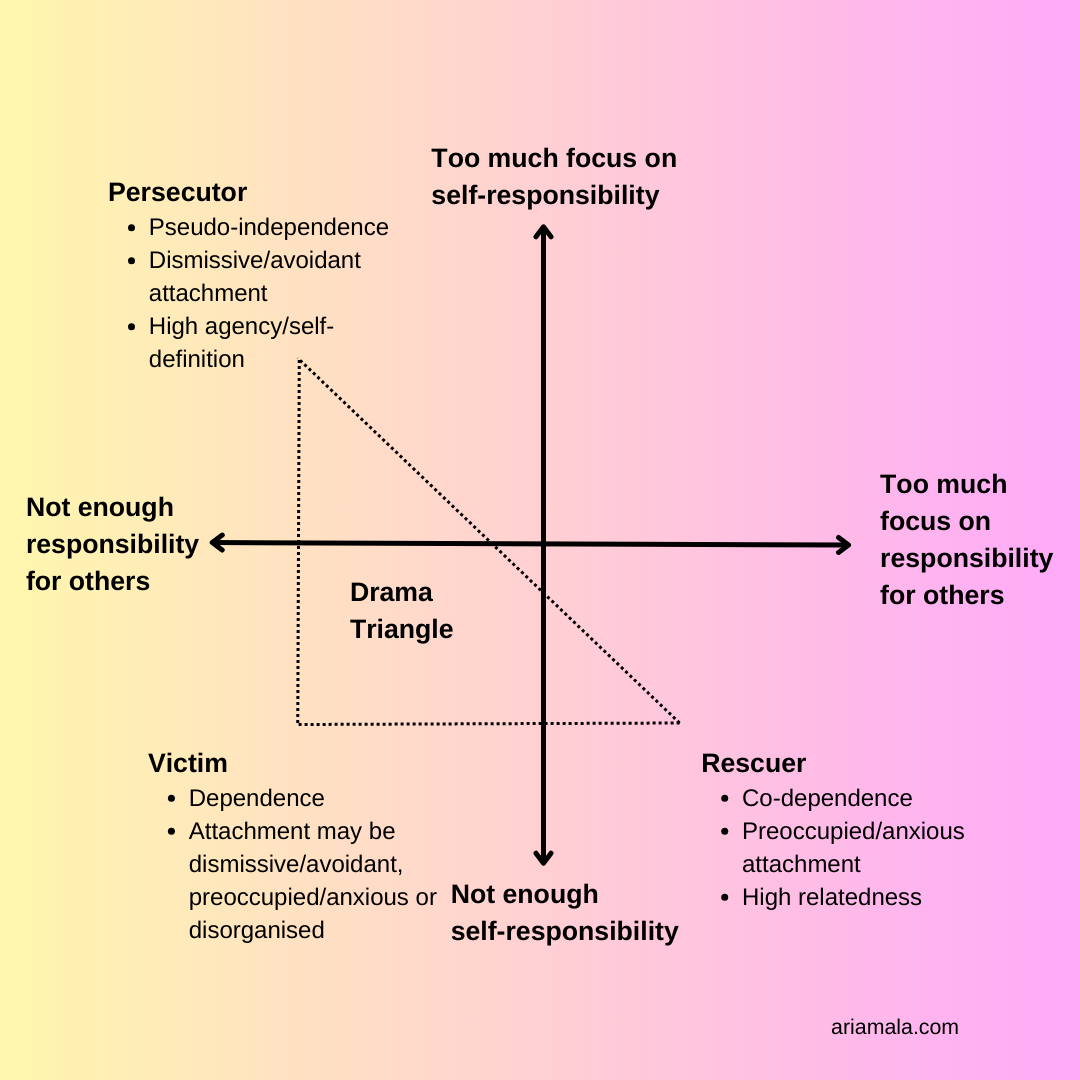

I mapped the drama triangle onto two axes of responsibility – self and other:

The Weight and Privilege of our Interdependence

This has been a long exploration on how to navigate and tolerate the inescapable truths of pain, impact and responsibility – because learning how to tolerate these truths has been and will continue to be, a lifelong exploration for me. I have spent a lot time trying to escape them but now I know there are no exceptions or exemptions. Everyone alive, including my puppy, will experience pain. Every being that exists will have an impact on the world. Knowing that we inevitably impact the world, we have a responsibility to the social systems and ecosystems to which we belong.

There are people who need to dial up their sense of responsibility and tread more lightly through the world and there are people who need to walk with less hypervigilance and more freedom. All of us need to tolerate the fact that being alive means impacting others. Our existence will leave a mark – whether it’s a hickey, an open heart or a broken heart.

However you usually walk through the world, don’t let your responsibility dial get stuck on one setting. Different relational contexts call for different responses. Lube up your dial and tune it accordingly.

Living this deeply relational, embodied and emotional life can be difficult to bear. Although the difficulty is unavoidable, an enhanced window of tolerance, a differentiated sense of self and a well-lubricated dial of responsibility can help us bear the weight and privilege of our interdependence.